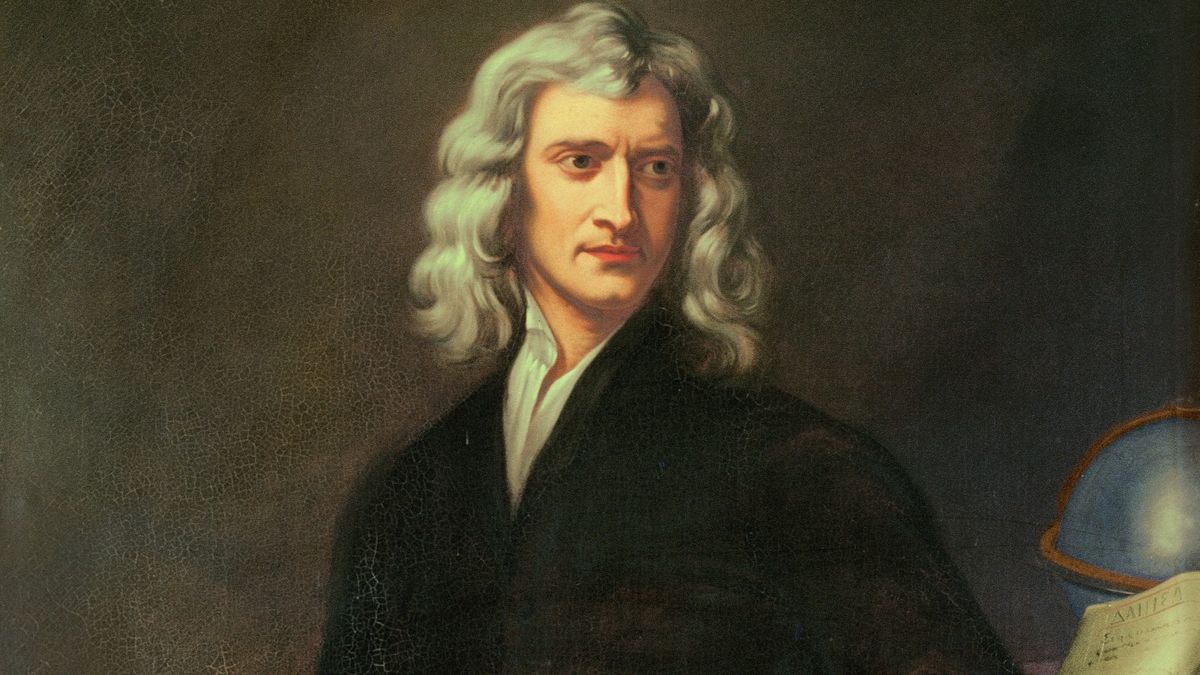

Sir Isaac Newton’s Third Law Of Motion posited that for every action in nature, there is an equal and opposition reaction. In other words, when two bodies interact, they apply force to each other. The Third Law holds that, for example, the force a tennis ball applies to a racket is equal and opposite to the force the racket applies to the ball.

Sir Isaac may have captured physical reality with his Third Law–without the action and reaction he recognized, for example, fish couldn’t swim and birds couldn’t fly–but his Third Law clearly doesn’t apply to the modern social media world. In case you haven’t noticed, a disproportionate amount of what we see presented as news isn’t about the underlying action, but instead is about the reaction. For every story about a particular incident–like a crime, a civic disturbance, a political figure being indicted, or an athlete being suspended–you’ll see far more stories, and memes, and “hot takes,” and all of the other modern ways of reacting to that particular incident, and the range of reactions will be across the board.

In short, the concept of an equal and opposite reaction is out the window, and I doubt that even Sir Isaac and his facility with mathematics (which included his invention of a new form of mathematics, called calculus) could come up with a formula to predict exactly what kinds of reactions a specific incident might generate.

I think the increasing focus on the reaction to the story, rather than the story itself, is a bad thing for two reasons. First, it’s lazy reporting. Actually digging into the underlying facts of an event, to help explain what happened and why, can be hard work, but collecting tweets or putting a third-party commentator on the broadcast to vent about an incident is an easy way to fill space or air time. And second, the focus on reaction clearly encourages overreaction. If you want your tweet to be featured in the inevitable reaction stories, you’ll be tempted to make your reaction as outrageous as possible, and if you’re a commentator, you’ll similarly be motivated to be over the top in your mugging for the camera. The focus on the reaction discourages thoughtful discourse–including waiting until all the facts come in before flying off the handle–in favor of the kind of splintered, superheated dialogue we see these days.

We’d be better off, in my view, if we stopped emphasizing the instant reaction and focused more on making sure we understand the facts and contours of the action.