I’ve always enjoyed the Sherlock Holmes stories and novels, but you can only reread the original tales penned by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle so many times until you thirst for something new. So lately, I’ve been dipping my toe into the broader Holmes universe, in which other authors have written tales of the great consulting detective of Baker Street and his solid, ever-dependable ally and biographer, Dr. Watson.

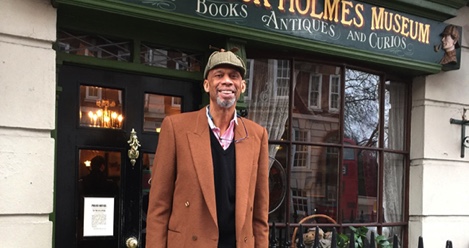

I recently finished a terrific set of short stories by Lyndsay Faye called The Whole Art of Detection: Lost Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes, in which I thought the author totally captured the voice of Dr. Watson and shed interesting new light on the relationship between Holmes and Watson. And get this: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is a devoted Sherlockian and is writing novels that focus on Holmes’ curious and brilliant older brother, Mycroft Holmes. That’s right — one of the greatest players in basketball history is said to be helping to reinvent the story of Sherlock Holmes. I’ve got one of Abdul-Jabbar’s novels, Mycroft and Sherlock, which he co-wrote with Anna Waterhouse, next up on my reading list.

I recently finished a terrific set of short stories by Lyndsay Faye called The Whole Art of Detection: Lost Mysteries of Sherlock Holmes, in which I thought the author totally captured the voice of Dr. Watson and shed interesting new light on the relationship between Holmes and Watson. And get this: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is a devoted Sherlockian and is writing novels that focus on Holmes’ curious and brilliant older brother, Mycroft Holmes. That’s right — one of the greatest players in basketball history is said to be helping to reinvent the story of Sherlock Holmes. I’ve got one of Abdul-Jabbar’s novels, Mycroft and Sherlock, which he co-wrote with Anna Waterhouse, next up on my reading list.

It’s fascinating that fictional characters like Holmes and Watson have had such profound staying power, to the point that multiple authors are writing about them more than 100 years after they were first created and became popular. In fact, those two residents of Baker Street may well be the most enduring characters in the history of literature. What other fictional creations have been written about for so long by such a diverse group of writers? I can’t think of any — can you?

You can argue about the greatest writers in literature, and few people would probably put the florid prose of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle up there with Shakespeare. But you’ve got to give Sir Arthur his due: when it comes to creating memorable characters, he’s arguably the greatest of all time.

It turns out that Russell and his Camp Seagull buddies had a lot in common with the ancient Sumerians, Shakespeare, and Jonathan Swift.

It turns out that Russell and his Camp Seagull buddies had a lot in common with the ancient Sumerians, Shakespeare, and Jonathan Swift. The answer is . . . a lot. According to

The answer is . . . a lot. According to