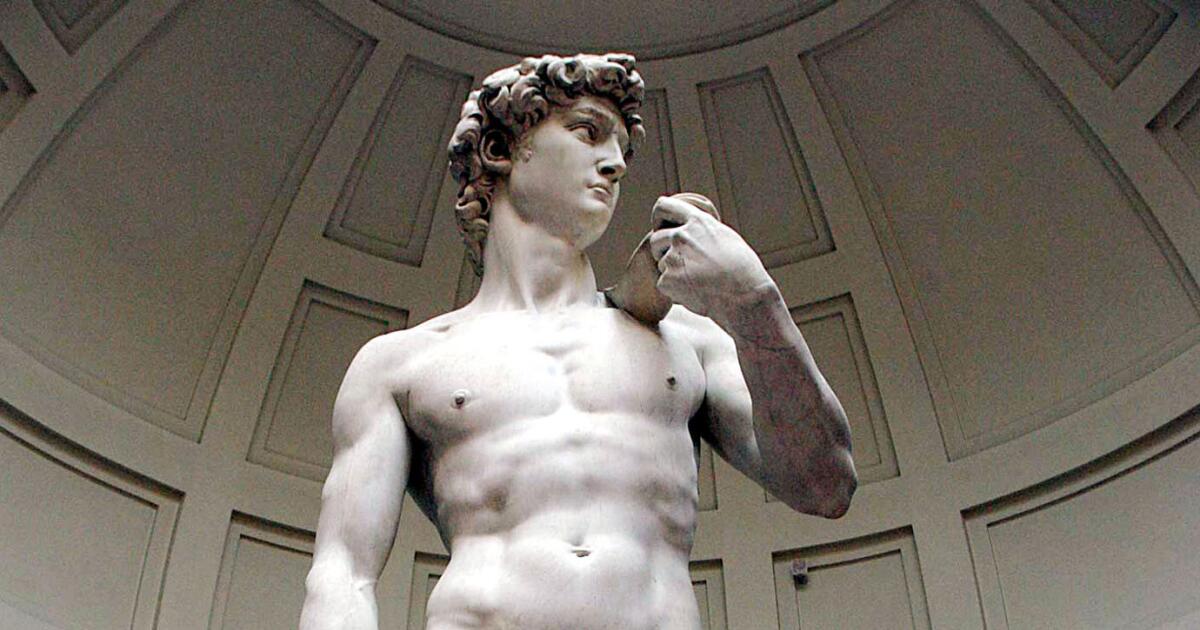

Michelangelo’s David is generally regarded as one of the supreme artistic creations in the history of the world. Housed in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, the colossal statue is breath-taking, magnificent, and inspiring. A visit to see David should be a bucket list item for any art lover.

David was completed in 1504, and in the 700 years since it has become an iconic image. Like any iconic image in the modern world, David has been commoditized. You can buy fluorescent plastic reproductions of the statue, t-shirts of David blowing a bubble or David hoisting a wine glass, or other goods featuring various parts of his body or face. But . . . is that proper? Or, should Italy be able to protect the dignity of this monumental artwork, and prevent it from becoming the subject of the kind of trashy junk sold in souvenir shops?

That’s an important question, because the director of the Galleria dell’Accademia has been using an Italian law to stop commercial exploitation of images of David that she considers to be “debasing.” She has encouraged the state’s attorney office to bring lawsuits under Italy’s cultural heritage code, which protects artistic works from disparaging and unauthorized commercial use. In most countries, artwork falls into the public domain within a set period after the death of the creator–and once a piece falls into the public domain, people are free to make use of its image. Interestingly, Italy is one of many countries that has signed a convention recognizing that approach.

The world obviously doesn’t need more cheap plastic knock-offs of David any more than it needs more t-shirts of the Mona Lisa wearing sunglasses–but there are obvious issues of free expression and free speech that also come into play. Who is to decide what is to be considered “debasing” or disparaging, or what should be authorized? Should Monty Python, for example, have been permitted to use the image of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus in a hilarious and arguably disrespectful way in one of its shows?

I come down on the side of free speech on this issue, and I think the notion of allowing artwork to pass into the public domain within a reasonable period after the artist’s death makes sense. And, at bottom, I really don’t think that the commercial uses of David are “debasing” of the artwork itself. I think that David, the Mona Lisa, Van Gogh’s self-portrait, and other supreme artistic accomplishments can withstand some crass commercial profiteering. If anything, that cheap neon plastic statue of David might just cause someone to want to go see the awe-inspiring original, in all its glory.

Now, it’s going to get even harder to distinguish the real from the fake. The development of artificial intelligence programming and facial recognition software is allowing for the development of increasingly realistic, seemingly authentic video footage that is in fact totally fictional. The

Now, it’s going to get even harder to distinguish the real from the fake. The development of artificial intelligence programming and facial recognition software is allowing for the development of increasingly realistic, seemingly authentic video footage that is in fact totally fictional. The

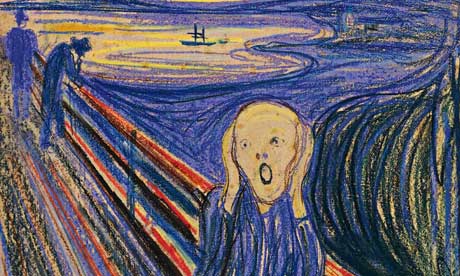

Munch painted four versions of The Scream in 1895. Three are in museums in Norway, Munch’s native land. The

Munch painted four versions of The Scream in 1895. Three are in museums in Norway, Munch’s native land. The

Italian authorities apparently have

Italian authorities apparently have  The painting, called “A Sacra Conversazione: The Madonna and Child with Saints Luke and Catherine of Alexandria,” sold for $16.9 million. The painting has all of the standard features of a “Madonna and child” painting — the plump but alert baby Jesus, wrapped in swaddling clothes, held by his placid mother Mary, who is clad in dark clothing. The only remarkable thing about the painting is that two other characters are shown, too.

The painting, called “A Sacra Conversazione: The Madonna and Child with Saints Luke and Catherine of Alexandria,” sold for $16.9 million. The painting has all of the standard features of a “Madonna and child” painting — the plump but alert baby Jesus, wrapped in swaddling clothes, held by his placid mother Mary, who is clad in dark clothing. The only remarkable thing about the painting is that two other characters are shown, too. she might be able to explain how Leonardo da Vinci was able to produce such a richly shaded depiction of her human face, without apparent brushstrokes, thumbprints, or other evidence of human creation. Until she speaks, however, we will leave it to science to gather evidence — which is what happened

she might be able to explain how Leonardo da Vinci was able to produce such a richly shaded depiction of her human face, without apparent brushstrokes, thumbprints, or other evidence of human creation. Until she speaks, however, we will leave it to science to gather evidence — which is what happened