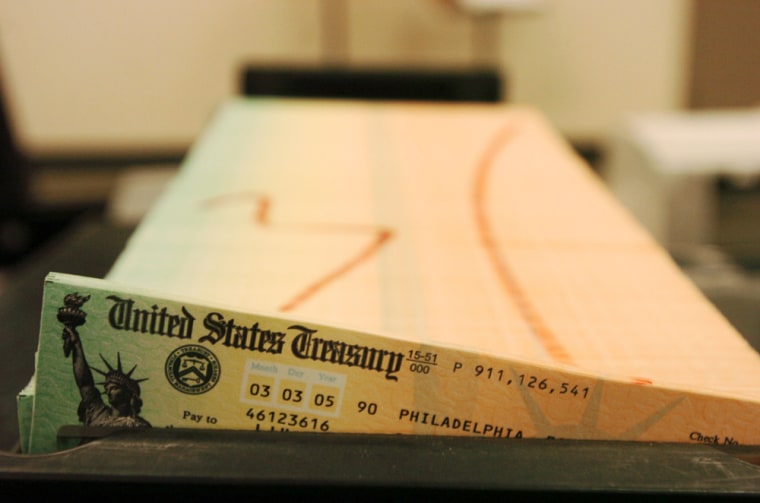

Last year, 401(k) employee retirement savings plans hit a venerable milestone — the 40th anniversary of their creation. 401(k) plans were born during the Carter presidency, with the passage of the Revenue Act of 1978, which established Section 401 of the Internal Revenue Code.

The language of the statute is the dense, definition-filled content that tax lawyers love, but the concept of the 401(k) is simple: workers can salt pre-tax money away in protected funds and invest it, thereby enjoying some tax savings and having a vehicle to save for retirement. Many employers offer 401(k) plans as a part of their benefit package and facilitate the program through payroll deductions. According to the Investment Company Institute, in 2016 there were almost 555,000 401(k) plans in the U.S. and more than 55 million Americans were active participants. The ICI also reports that, as of the end of the third quarter of 2018, 401(k) plans held $5.6 trillion in assets — up from $2.2 trillion in 2008 — and represented 19 percent of the total amount of U.S. retirement assets.

The language of the statute is the dense, definition-filled content that tax lawyers love, but the concept of the 401(k) is simple: workers can salt pre-tax money away in protected funds and invest it, thereby enjoying some tax savings and having a vehicle to save for retirement. Many employers offer 401(k) plans as a part of their benefit package and facilitate the program through payroll deductions. According to the Investment Company Institute, in 2016 there were almost 555,000 401(k) plans in the U.S. and more than 55 million Americans were active participants. The ICI also reports that, as of the end of the third quarter of 2018, 401(k) plans held $5.6 trillion in assets — up from $2.2 trillion in 2008 — and represented 19 percent of the total amount of U.S. retirement assets.

Some people raise questions about the 401(k) option, arguing that its availability has helped to produce the virtual disappearance of employer-funded pension plans, in which the employer totally funded the plan and, in many instance, provided the employee with a guaranteed retirement benefit. I think that’s wishful thinking. Even at the time the 1978 legislation was passed, many American companies were looking to cut costs, and guaranteed pension plans were disappearing into the mists of history. Most of us have never worked for an employer that offered a true pension plan. To be sure, 401(k) plans are based primarily on employee contributions, not employer largesse — although in many cases employers offer some kind of match to employee contributions.

Unless you’re an investment advisor who pines for the long-lost days of funded pension plans, though, you’re probably grateful that Congress was far-sighted enough to create the 401(k) option 40 years ago. And it’s not hard to argue that 401(k) plans are, in some respects, superior to pension plans. The 401(k) option gets the worker directly involved in her own retirement planning; employees have to elect to participate in the plan, after all, determine how their contributions will be invested, and then have their contribution withheld from their paychecks. The 401(k) mechanism makes that as painless, relatively speaking, as withholding for federal and state taxes and Social Security contributions — because it comes out automatically, most people don’t notice it. And then, after a few years, workers realize that they’ve actually made progress in starting to save for retirement, and for many people that realization opens the door to additional efforts to save, invest, and get ready for the retirement years. The 401(k) option has made many Americans take personal responsibility for their own financial affairs, rather than relying on a company pension plan to do the trick.

And you can argue that 401(k)s have had a broader benefit, too. So much automatic saving has to be invested somewhere — principally in the U.S. stock market. In 1978 the Dow was well below 1,000; now it stands above 25,000. No one would argue that 401(k) plans have been solely responsible for that run up, but there is no doubt that they have contributed to buy-side pressure that has helped to move the stock market averages upward, which has the incidental benefit of helping all of those 401(k) participants who’ve put their retirement savings into the market in the first place.

Happy anniversary, 401(k)! Beneath that Tax Code jargon lurks an idea that has been helpful to millions of Americans. I’d say we need to give credit where credit is due: the 401(k) is one time when Congress did the job right.

The secret issue is this: in “boomer” households where one spouse works outside the home and the other doesn’t, the forced “shelter in place” requirements are seen as a kind of trial run for the retirement period that is coming down the road in the near future. And neither spouse really knows, for sure, how it’s going to work when the one spouse stops trotting off to work on weekdays and ends up hanging around the house with the other spouse all day. To be sure, they hope that the retirement years will be the golden period of bike-riding and pottery-making togetherness that the commercials depict, but they wonder if the reality is going to be more difficult . . . and darker.

The secret issue is this: in “boomer” households where one spouse works outside the home and the other doesn’t, the forced “shelter in place” requirements are seen as a kind of trial run for the retirement period that is coming down the road in the near future. And neither spouse really knows, for sure, how it’s going to work when the one spouse stops trotting off to work on weekdays and ends up hanging around the house with the other spouse all day. To be sure, they hope that the retirement years will be the golden period of bike-riding and pottery-making togetherness that the commercials depict, but they wonder if the reality is going to be more difficult . . . and darker. I decided to check that out, and learned two things. First, The Villages is so big it has its own newspaper, at Villages-News.com. And second,

I decided to check that out, and learned two things. First, The Villages is so big it has its own newspaper, at Villages-News.com. And second,  The Bloomberg article linked above suggests that many of these working elderly are doing so because they have no choice: “Rickety social safety nets, inadequate retirement savings plans and sky high health-care costs are all conspiring to make the concept of leaving the workforce something to be more feared than desired.” But the statistics indicate that at least some of the people who are working longer are doing so by choice, rather than by desperate need. The share of all employees age 65 or older with at least an undergraduate degree is now 53 percent, up from 25 percent in 1985, and the inflation-adjusted income of those workers has increased to an average of $78,000, 63 percent higher than the $48,000 older folks brought home in 1985. The increase in wages of the working elderly is better than the increase for workers below 65 during that same time period.

The Bloomberg article linked above suggests that many of these working elderly are doing so because they have no choice: “Rickety social safety nets, inadequate retirement savings plans and sky high health-care costs are all conspiring to make the concept of leaving the workforce something to be more feared than desired.” But the statistics indicate that at least some of the people who are working longer are doing so by choice, rather than by desperate need. The share of all employees age 65 or older with at least an undergraduate degree is now 53 percent, up from 25 percent in 1985, and the inflation-adjusted income of those workers has increased to an average of $78,000, 63 percent higher than the $48,000 older folks brought home in 1985. The increase in wages of the working elderly is better than the increase for workers below 65 during that same time period. Increasingly, however, older Americans are breaking that very basic rule. It’s part of a growing and worrying trend of accumulating credit card debt, and delinquency, by Americans.

Increasingly, however, older Americans are breaking that very basic rule. It’s part of a growing and worrying trend of accumulating credit card debt, and delinquency, by Americans. The language of the statute is the dense, definition-filled content that tax lawyers love, but

The language of the statute is the dense, definition-filled content that tax lawyers love, but  Most of the retirement materials you receive are just a variation on the kind of stuff you’ve probably received for years, that talk up some great investment opportunity that is so bullet-proof you’d be a fool not to put your money in, or promise to take great care of your savings and lead you to the retirement of your dreams. For me, those kind of “cold call” communications get moused into the trashcan. But sometimes you see something that’s actually interesting — like

Most of the retirement materials you receive are just a variation on the kind of stuff you’ve probably received for years, that talk up some great investment opportunity that is so bullet-proof you’d be a fool not to put your money in, or promise to take great care of your savings and lead you to the retirement of your dreams. For me, those kind of “cold call” communications get moused into the trashcan. But sometimes you see something that’s actually interesting — like  Uncle Mack is one of those people who has always been “involved.” When he lived in Reston, Virginia, he was active in leadership positions with community organizations and was featured in a full-page news article. (The article referred to Uncle Mack as a man in “triple focus,” because of his many activities, and had a three-exposure picture of him. It was a very nice article, but the “triple-focus” description cracked me up and has always stuck with me. Now, whenever I see UM, I try to work in a gratuitous “triple-focus” comment just for the heck of it. Now I’ve been able to work it into this blog post, too.)

Uncle Mack is one of those people who has always been “involved.” When he lived in Reston, Virginia, he was active in leadership positions with community organizations and was featured in a full-page news article. (The article referred to Uncle Mack as a man in “triple focus,” because of his many activities, and had a three-exposure picture of him. It was a very nice article, but the “triple-focus” description cracked me up and has always stuck with me. Now, whenever I see UM, I try to work in a gratuitous “triple-focus” comment just for the heck of it. Now I’ve been able to work it into this blog post, too.) Sometimes the articles can be a bit . . . alarming. Like

Sometimes the articles can be a bit . . . alarming. Like  It’s an interesting milestone, and one that is very pleasing to the millions of Americans who have money invested in stocks or mutual funds. Investment in the stock market — especially through managed mutual funds — is one way the average American can put money away for retirement and (we hope) earn a decent return on our savings. Over its history the Dow has been pretty dependable in that regard, overcoming periodic drops and crashes and showing significant long-term increases both

It’s an interesting milestone, and one that is very pleasing to the millions of Americans who have money invested in stocks or mutual funds. Investment in the stock market — especially through managed mutual funds — is one way the average American can put money away for retirement and (we hope) earn a decent return on our savings. Over its history the Dow has been pretty dependable in that regard, overcoming periodic drops and crashes and showing significant long-term increases both  If you do go to the Columbus Arts Festival this weekend, be sure to stop by the Cultural Arts Center and vote for the terracotta bust created by my friend, the Talmudic Sculptor. His piece — which he’s left untitled, but which I think should be called Wide-Eyed Woman — is number 308 in the exhibition. The CAC is having a kind of “people’s choice” vote and, as the T.S. mentioned, any vote for his creation is one more vote than he would have gotten otherwise. (That kind of subtle wisdom is why he’s got the “T” in his name.)

If you do go to the Columbus Arts Festival this weekend, be sure to stop by the Cultural Arts Center and vote for the terracotta bust created by my friend, the Talmudic Sculptor. His piece — which he’s left untitled, but which I think should be called Wide-Eyed Woman — is number 308 in the exhibition. The CAC is having a kind of “people’s choice” vote and, as the T.S. mentioned, any vote for his creation is one more vote than he would have gotten otherwise. (That kind of subtle wisdom is why he’s got the “T” in his name.)